STANLEY E. STOCKINS

Born: St. Paul, Minnesota, 1916.

H&W: 5’10” 135 lbs. (178 cm / 63 kg)

S/N: 20616538

Enlisted: March 5, 1941, 124th Field Artillery, 33rd Infantry Division, Chicago, IL.

Unit: Supply, H Company, 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

Resting Place: Plot H, Row 1, Grave 21, Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, Colleville-sur-Mer, France

Stanley's early life

Stanley E. Stockins was born in St. Paul, Minnesota in the summer of 1916. His father, also named Stanley Stockins, was an immigrant from London, England. His mother, Emily was also from England. The couple met in St. Paul, where they married on October 27th, 1915. Shortly after their son Stanley’s birth, an offer to take over a family home in Chicago gave Mr. and Mrs. Stockins the opportunity to grow their family. They moved to a house at 7119 South University Avenue (on the corner of 71st and South University Avenue), where they had a son Howard in 1918, and daughters Marjorie in 1922 and Arlene in 1937. Mr. Stockins, who had worked as a janitor in St. Paul, took up work as a laborer, laying bricks at the South Side Steel Works.

Stanley grew up in the Greater Grand Crossing neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side, in the Stockin’s family house, which was located directly across the street from the Oak Woods Cemetery. He attended Paul Revere elementary school and graduated from Hirsch High School (probably the class of 1933, 34 or 35)

Like millions of other families in America during the Great Depression, the Stockins family struggled financially. Health issues forced Stan’s father to retire early, placing the burden of providing for the family upon Stan and his younger brother Howard. The two brothers pooled their money to purchase a wooden cart, which they used to sell fruit in the alleys of Chicago.

After Stanley graduated from Hirsch High School he joined the Civil Conservation Corps (CCC), a public work relief program born from President Roosevelt’s New Deal. The CCC gave young men the opportunity to work out in the fresh air, where they planted trees, built parks, modernized state parks, built roadways and service buildings. For this they were paid a salary of $30 a month, of which $25 were sent home to their families.

In the autumn of 1935, while working at the China Flats camp near Powers, Oregon, Stanley was involved in an accident. At 2 a.m., Stanley and 22 other CCC workers were returning from fighting a forest fire when the driver lost control of the truck and it rolled down a 30 foot embankment. Despite having two broken ankles, Stanley took charge of the situation and “directed first aid work until all of his companions had been removed from the wreckage.” For this heroic act he was awarded an official commendation for bravery by the US War Department.

Stanley returned to Chicago and took a job as an electrician’s helper at US Steel South Works to help support his family. Stanley’s father’s health worsened and gangrene, probably from diabetes, forced the amputation of both of his legs. Stanley continued to pitch in the best he could, keeping what little money he could put aside to buy a motorcycle and to take his girlfriend Peg on dates.

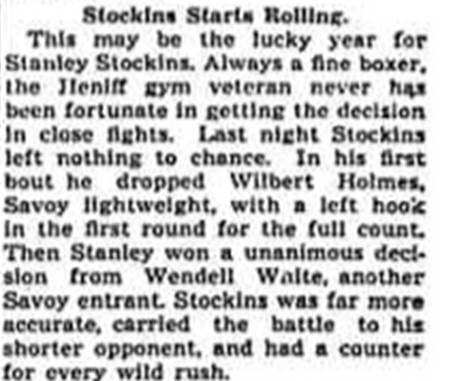

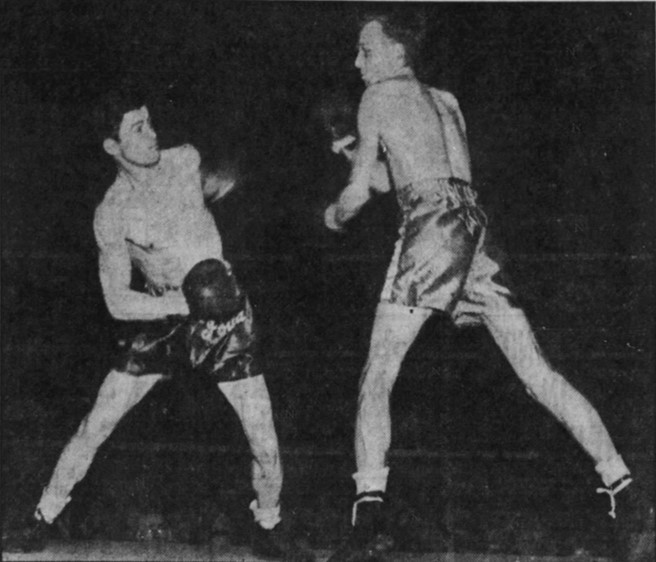

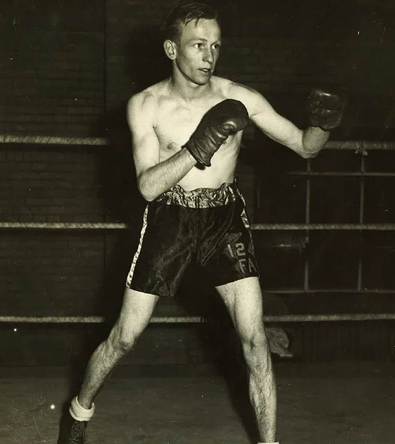

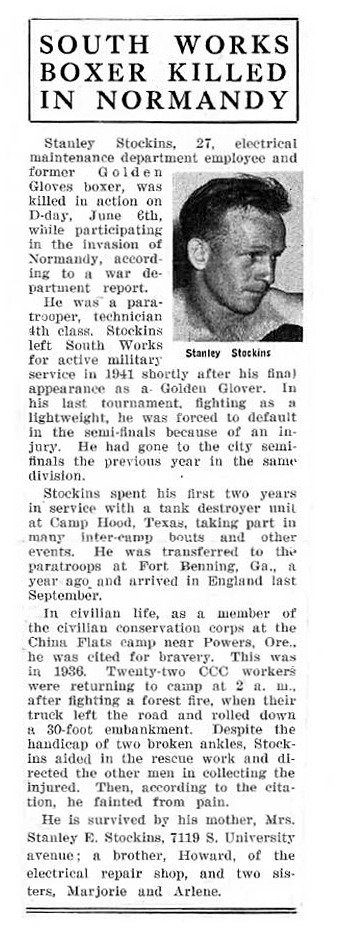

Stanley’s greatest passion was boxing. He began boxing in the mid-1930s, working out at St. Pat’s and Heniff’s gyms. His amateur bouts at the Madison Athletic Club in Chicago were reported on in the Chicago newspapers. In 1940 & 1941 Stanley made it all the way to the semifinals in the Golden Gloves.

From the Chicago Daily Tribune, February 18, 1941

In the years just before the war, Stanley worked hard, trained hard and tore up Chicago’s South Side on his motorcycle. Ever the daredevil, it was inevitable that he would crash the motorbike. Fortunately he never sustained any injuries serious enough to threaten his career in the ring. Stan fought his last amateur fight in 1941, shortly before deciding to join the army.

Enlistment

On March 5, 1941, the Illinois National Guard’s 33rd Infantry Division was called into federal service. Stanley enlisted on March 5th, 1941, and was assigned to the 124th Field Artillery Battalion. His orders directed him to Camp Forrest in Tullahoma, Tennessee for basic and advanced training. Stanley served as an anti-tank gunner in Battery K.

In the spring of 1941, tragedy struck the Stockins family when Stanley’s father died of complications due to his illness. The Red Cross paid for Stanley’s trip home from training in Tennessee so he could attend his father’s funeral. While home on that visit, his four year old sister Arlene received a new pair of roller-skates. To this day she loves to tell the story of how her 25 year old brother, dressed in his crisply pressed army uniform, laced her skates to her shoes and gently held her hand as he guided her around the entire block. She was so proud of her older brother. It would be the last time she ever saw him.

Saying goodbye to his family, Stanley returned to the 124th Field Artillery. In 1942 his unit moved to Fort Hood, Texas. Then, in the summer of 1943, Stanley wrote to his mother telling her that he was considering joining the paratroops. Mrs. Stockins was resolute: there was no way a son of hers was going to risk his life jumping out of airplanes. However, by the time she finished her response to this effect, she received another letter from Stanley announcing that he was already working on earning his jump wings at Fort Benning, Georgia. It was official: Stanley was a proud member of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne.

Stanley’s next stop was Ramsbury, England, where in the autumn of 1943, he was assigned to the supply section of H Company. In addition to rigorous field training in preparation for the upcoming invasion, Stanley continued to box. While stationed in England, Stanley fought a total of 14 bouts, of which he won 11. Happy to be back in the ring, and full of enthusiasm for his beloved sport, he wrote home telling his family that if he could fight at least two professional bouts after the war, he would be able to realize his lifelong dream of becoming a confirmed prize fighter. Along with the letter, he included two of his recently earned boxing medals. To his 8 year old sister Arlene, he sent a heavy china mug depicting the famous British character John Bull, which she still cherishes to this day. While Stanley was in England he enjoyed sightseeing in London, and reconnecting with distant family members. He also wrote home to his girl Peg back in Chicago. She assured him she’d be waiting for him when he returned to her after the war.

D-DAY

Stanley’s time in England came to an end on the evening of June 5th, 1944, when he boarded his C-47 for the night flight over the English Channel. Stanley’s plane number is unknown and therefore it is difficult to know the details of his D-Day flight. He was later reported as helping to pull fellow paratroopers to safety from the swamp of a flooded field in Normandy, so it can be gathered that his jump was successful and he landed and freed himself from his harness unharmed.

In the early morning hours of June 6th, Stan linked up with a group of soldiers from H Company and headed toward the road bridge between the Fortin farm and the town of Brévands. The group was commanded by 1st Lt. Christianson, and included fellow supply sergeant S/Sergeant Fred Bahlau and other members of H Company. 250 paratroopers were supposed to rendezvous and position themselves at the road bridge, but due to casualties and missed drops only about 40 paratroopers made it.

At approximately 05h30, 1st Lt. Christianson sent a small patrol across the Douve River to the south side, which was occupied by the Germans. The patrol was to draw enemy fire in order to measure the enemy’s strength. The patrol included Fred Bahlau, who made it across the river, but then came under intense fire and was forced to return.

What happened next is told in Chapter 7, in the excellent book, Tonight we Die as Men, Gardner & Day:

In support of S/Sgt. Bahlau and the others from his patrol, Sgt. Bennett of the mortar squad ordered Stanley to throw blocks of C2 explosives across the Douve River at the Germans. Stanley had to insert slow burning waterproof fuses into the ends of each heavy (1lb) C2 block and then pause momentarily before throwing them as far as he could…. Suddenly Stockins stopped throwing the explosive. He had been hit in the face by a German bullet and died instantly. Pvt. McCann was nearby and saw what happened. ‘Stockins had stayed in the same position for too long and the Germans had a bead on his location. I think the bullet hit his (Thompson) submachine gun in the breech area and ricocheted up through his face.’ Ed Shames was the first person to reach him. ‘I think the shot came from a two-story house across the river. I turned him onto his back and dealt with his dog tags. Then Father McGee came across and said a few words.’

Fred Bahlau’s version of Stanley’s death is slightly different. It is told this way on Mark Bando’s website Triggertime:

“On D-Day, shortly after returning from the German-held south bank of the Douve River near Brévands, France, Fred had taken-up firing position just to the left of Stan Stockins on the north berm. Some of the troopers present were briskly exchanging shots with the Germans across the river. Suddenly, a German bullet struck Stockins a fatal wound to the head. Seeing this happen from less than 2 feet away was a traumatic experience for Fred.”

Later that month, back home in South Side, Chicago, Mrs. Stockins received the Western Union Telegram informing her of her son Stanley’s death.

Shortly before Stanley boarded his C-47 at Exeter airfield, he made sure his GI life insurance was in order. This bit of administration could have easily been overlooked, but instead it provided his mother with the $10,000 she needed to feed and shelter her family. Mrs. Stockins always knew her beloved son Stanley would be there for her. He had taken such good care of his family during the Depression, especially when his father was ill. He always did whatever he could: he sold fruit, he moved away to work in the CCC, and even through the darkest days of the Depression he managed to hold his job at US Steel South Works. This last gesture of responsibility and selflessness came at the most terrible cost imaginable, but it was typical of Stanley and it illustrates all at once his love for his family and his sense of duty. Stanley had the fighting spirit of a boxer, the grit and courage of a paratrooper and the generous heart of a loving son and brother.

Stanley rests in Plot H, Row 1, Grave 21 in the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, France.

Thank you, Stanley, for your sacrifice.

_large.jpg)

I promise to remember.