Philip Germer

Born: Trinidad, Colorado, October 29, 1923

H&W: 5’9” 143 lbs. (175cm / 69 kg)

S/N: 17091587

Enlisted: September 10, 1942. Volunteered for the Airborne

Unit: Light Machine Gun Platoon, Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division

Nickname: Germer

Resting place: Plot C, Row 28, Grave 30. Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, Colleville-sur-Mer, France

Philip's early life

Philip Germer was the grandson of German immigrants who came to America in 1880. Following the birth of a son Melvin in November 1880, his grandfather Philip and his grandmother Minnie moved west and settled in Trinidad, Colorado, just a few miles north of the New Mexico border.

In 1894 Philip and Minnie became naturalized American citizens. Their son Melvin grew up in Trinidad and became a railroad freight handler and signal man. He married Dora Lucero and together they had seven children: four girls and three boys. On October 29, 1923, Dora gave birth to their fourth child and second son. They named the boy Philip after his grandfather.

Philip attended Trinidad High School, and played on the school’s golf team. He graduated in the class of 1941. While at Trinidad High, Philip began dating a beautiful Italian redhead named Esther Dipaolo, who later became his fiancée.

After high school Philip was just itching to get out of Trinidad. His older sister Virginia, who had already moved out to California, encouraged him to come join her for a while. Philip packed his bags and headed west. It wasn’t long before he found a job working as a soda jerk at Thrifty Drug in Santa Monica. Philip’s broad smile, natural charisma, and keen sense of humor made him a star at the soda fountain. By day he whipped up milkshakes and ice cream sodas for the pretty girls of Santa Monica, Beverly Hills and Hollywood; by night he danced to live Big Band music at the hottest local clubs. By the end of the summer of ’42 Philip must have seen one soldier too many pass by his soda fountain in a brand new uniform, because in September he decided it was his turn to join the army.

Before enlisting, Philip returned to Trinidad to spend some time with his family and Esther. Then, on September 10th, 1942, Philip Germer, the 19 year old soda jerk and all-American boy, went to Pueblo, Colorado and volunteered for the most dangerous job in the military: jumping out of airplanes into combat.

Training at Toccoa, Benning and Mackall

Philip was ordered to report for Paratrooper training in Camp Toccoa, Georgia, where he was then assigned to the Light Machine Gun platoon of Headquarters Company, 3rd battalion, of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. After training at Camp Toccoa from September 1942 until late November 1942, Philip and the 506th were sent to Fort Benning, Georgia for parachute jump training. This is where Philip made his five qualifying jumps and earned his paratrooper wings. The 506th then moved to Camp Mackall, North Carolina for night jump training. In his light machine gun platoon Philip developed close friendships with Fayez Handy and George “Doc” Dwyer.

Dwyer described Phil this way: “‘Germer’ (that is what everybody called him), was always good natured and smiling or laughing, and playing jokes on his buddies, but hard working when it came to our training requirements, which were strenuous, to put it nicely. One thing I will always remember about Germer: When we were in Camp Mackall our barracks were right next door to the Mess Hall, and it was always a race in the morning to get to the table and be the first to corner the fresh milk (which was scarce), and Germer seldom lost that race!”

Fayez Handy liked to tell stories of how Philip was a top notch jitterbug dancer, and how when they would go dancing Philip would steal the show.

Philip Germer in Camp Tocca, Georgia, 1942.

On June 1st, 1943 the 506th was officially attached to the 101st Airborne Division. Later that same month the 506th participated in the Tennessee maneuvers, where they worked extensively on field training. In August 1943, the 506th PIR was ready for overseas deployment. They were first sent to Ft. Bragg to be fitted out with uniforms and equipment, and then made their last domestic transfer to Camp Shanks, New York, where they staged in preparation for their transatlantic voyage en route to the European Theater of Operations. On September 15th,1943, one year and five days after he’d volunteered for the paratroops, Philip arrived in Liverpool, England aboard the S.S. Samaria.

Pre-D-Day and D-Day

On May 27th, 1944, Philip’s 3rd Battalion of the 506th quietly left their English camp at Ramsbury for the pre-invasion marshaling area at Exeter airfield. While there, the soldiers were issued “invasion money” in the form of French Francs. Philip’s platoon leader 1st Lt. Bill Wedeking asked his men to sign one of his 100 Franc notes. On the morning of Monday, June 5th Fayez Handy came to Philip and told him there was about to be a religious service and asked if he’d come along. At first Philip declined, but then changed his mind and went with his best friend to attend the mass, where he received absolution from the priest. For many paratroopers who attended that open air service, it would be their final moment of peace on earth.

Later that afternoon Philip’s platoon had the pleasure of meeting General Eisenhower, as he paid the Airborne paratroopers a special visit, joking with them and wishing them luck. George “Doc” Dwyer called Eisenhower’s visit “quite an emotional moment.”

With the black and white paint of the invasion stripes still fresh on his plane’s wings and fuselage, Philip climbed the steps toward the open door. He was loaded down with almost as much weight in gear as he weighed himself. Just to the right of that door, a large number drawn in white indicated Philip’s jump stick number. Philip was in “chalk 5,” along with 1st Lt. Bill Wedeking, Sgt. George “Doc” Dwyer, and his friend Fayez Handy.

Philip’s platoon of 40 men and two officers was divided into two jump sticks. 1st Lt. Bill Wedeking and Sgt. George Dwyer led Philip’s 16 man stick. Philip was assigned to the number two spot in the stick. That meant that once the pilot switched on green light at the door signaling to the jumpmaster to give the order to jump, Philip would be the second man out the door.

As the men took their places in the steel seats lining the plane’s walls, they were handed two “air-sickness” pills and instructed to swallow them. Whether these pills were for air-sickness or just to calm their nerves is unknown.

Philip’s number five plane taxied and took off from Exeter airfield just before midnight. Once aloft number five didn’t head straight for France, but initially circled the airfield waiting for the following 40 C-47s in its group to get airborne and join the flight formation. The planes took off in 10 second intervals; the entire group was up and over Exeter field within 8 minutes.

It wasn’t long before the air-sickness pills began to have different effects on the men. Some began to doze, and others, who found the medicine made them sick, had to stand up and stumble to the rear of the plane to vomit.

Chalk five’s C-47 droned on toward its destination, the sound of its engines drowning out all but a man’s thoughts. Communication between the soldiers, if there was any at all, had to be made in gestures. A nod and an attempt at a reassuring smile, a pat on the arm, the lighting of a cigarette. While the lucky ones dozed, others double and triple checked their gear and tried to anticipate combat scenarios—the M2 switchblade knife that hung from the neck and slipped into a small chest pocket, the M3 jump knife tied to the outside ankle of the jump boot: could they be reached in time to cut the risers, the harness, or another man’s throat? Some men clicked their shiny new “crickets”; others tightened the strings on the supplementary first aid kits they’d tied to their helmet webbing, shoulder straps or their arms or ankles.

Through the ink black skies over the English Channel, vibrating from the roar of the two Pratt & Whitney radial motors and jostling shoulder to shoulder with his fellow paratroopers, what was Philip thinking about? Was he thinking of his family back home at 1521 North Denver Street, and how they knew nothing of what was about to happen, about what he was a part of and how it was going to change history? Was he thinking of his fiancée Esther? Or was he trying not to think by quietly humming the words to his favorite song “I’ll get by (as long as I have you).” Philip must have considered the irony of his voyage. This twenty-year-old grandson of a German immigrant was now returning to Europe sixty-four years after his grandfather had left it to start a new life in America. When his boots touched down on European soil, would he not be making family history? When he fired his weapon at the enemy, might he be firing upon a distant relative?

When his C-47 reached the heavily defended coast and came under the violent anti-aircraft fire that lit the night and tossed the plane about in the sky, Philip rose to his feet, when the red light came on and the order came to “stand up and hook up.” Standing just two feet from the open door, he braced himself, felt the violent wind beating his face, watched the fire in the night, felt the pilot struggle to keep the plane in formation, while avoiding the fierce ground fire. When the equipment check came down the line, he shouted “Two OK” and nodded to his jumpmaster that he was ready. It was time. They were over land now and flying low. The ground fire intensified. The plane shook, jolted, rose and dipped. The green jump light flashed on, and the order shouted to “Go! Go! Go!” Phil hurled himself through the open doorway and into the void. He must have felt the brutal smack of the prop blast, then the bone jarring, but reassuring jolt of his parachute as it opened above him. He probably glanced up to check his canopy panels, then looked down to the field below him.

What Philip saw next we shall never know, but the sight must have been horrifying, for chalk 5 jumped directly over a heavily fortified German camp. When Philip’s chute opened it created a bright backdrop against the night sky. As he floated earthward, he was an easy target for the enemy soldiers who fired mercilessly upon him from below.

Several days later Philip was found along with so many other unfortunate paratroopers, in a field near Saint-Côme-du-Mont. He was still in his parachute harness. It is likely he was machine gunned to death before he even reached the ground.

The field where Philip Germer was shot and killed. June 4th, 2015

In December 1943, Philip wrote to his family from Fort Benning, Georgia. In his letter he mentioned that he loved the new song by Bing Crosby called “White Christmas.” For the rest of her life, whenever Christmas came and that song played on the radio, Philip’s sister Mary would shut off the radio and cry with an aching sadness from the bottom of her heart.

Philip was originally taken to the temporary cemetery at Hiesville on June 10th, before being moved to the nearby Blosville cemetery on July 4th. In 1947 the government began the process of moving the soldiers buried at Blosville to the American cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. At this time the Germers were offered the opportunity to repatriate Philip’s remains. Philip’s parents decided to let their son rest alongside the men he served with and loved as brothers. Philip was moved to Colleville in 1949.

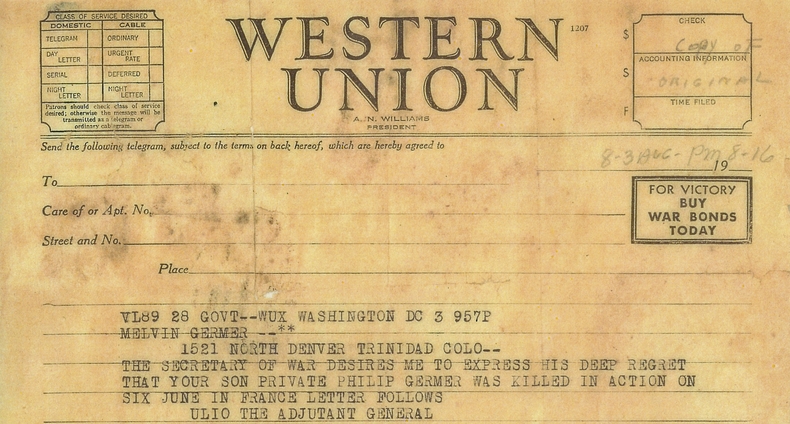

Philip was survived by his parents and his six siblings. When the telegram announcing Philip’s death came to the Germer’s house, his family was so devastated that in their moment of grief they forgot to inform his fiancée Esther. She learned the terrible news in the local newspaper the next day.

In 1970, Philip’s sister Mary traveled to Normandy to visit his grave at the American Cemetery; she left a single red rose at the base of his cross.

Philip rests at Plot C, Row 28, Grave 30.

I promise to remember.